Lake Success

What is success for an active manager? It really boils down to two things. Generating alpha, and growing assets. In an ideal world, the two are symbiotic. In reality, they often conflict. That conflict is a persistent trend that most people don’t publicly speak about. It becomes normal in our little nexus of the universe. Sometimes an outside perspective does the best job of shaking us out of a stupor. I recently started reading Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart, a fictional author whose book ostensibly focuses on Manhattan-based hedge fund culture. It wasn’t the hilarious youtube video that got me to pick it up (that didn’t hurt). I stumbled upon it during an impromptu trip to a bookstore while on a work-trip.

For a quantitative asset manager such as ourselves, work trips are almost exclusively to meet capital allocators (versus say company management). We (active managers) go on these trips to drum up interest on the uphill trail of raising capital. It’s quite a lot of effort securing allocations from institutional investors and with good reason. As fiduciaries, they must carefully examine investment opportunities and be true stewards of their constituents’ capital. The stakes are high and the search costs are real. There isn’t a facebook for alpha.

How to Win Friends and Influence People

The dance is in many ways an exercise in relationship building. But that exercise has logically gone down a competitive path. It has some perverse tendencies and consequences. It can promote salesmanship over investment skill. It taxes organizations away from their core competence. It incentivizes braggadocios given the outsized financial remuneration at stake. In Lake Success, our main character [Barry Cohen] is a hedge fund manager who has practiced courting influence since he was in middle school. It didn’t come natural; it was a muscle he developed. Or in the author’s words, it was programmed. He did it because he knew that smarts weren’t quite enough. Networking and being liked were the keys to success:

When Barry was a kid, he had been super smart. He could program his Commodore 64 to make a graphic of the USS Enterprise from Stark Trek gliding from one side of the screen to the other. But he knew that if he wanted to get out of Little Neck, out of his father’s tropical basement, he had to make friends. So each day, he’d stand in front of the mirror and practice ten opening lines that he could say to the other boys in homeroom, the boys who didn’t know he existed…

This is not to say that social skills are a bad thing. But they can be manipulated into an optimization exercise: customer acquisition cost. Acquisition for something as mercurial as alpha generation is a function of convincing. The ability to convince is strikingly important in our business. The truly convincing are often the most brazen and often don’t rely on logic but passion.

The book is in quite postmodern in its treatment of logos vs pathos. It completely disregards the skill part of the equation, focusing instead on the signs of skill (where one went to school, where one did their IB stint, where one vacations, where one lives). It’s main character (the multi-billion dollar hedge fund manager) doesn’t even believe in skill. He believes in mythmaking:

“You want to know the first rule of running a billion-dollar-plus hedge fund? Don’t sweat the metrics. We’re not really about the numbers. Do you know what we are? We are a story. Hedge funds are a story about how we’re going to make money. They’re about being smart, gaining access, associating with someone great. You. You are someone smart enough to make others feel smart. You are bringing your investors something far more elusive than a metric. You’re bringing them the story of how great you’ll be together.”

The Skeptic’s Toolkit: Testing for Truth

The opportunity at play for storytellers like Barry means allocators must have their armor up and their skepticism on high alert. Like an investigative journalist, they have to weed out the truth. Doing so ratchets up the stakes of the game. Mind you, this is a challenging game, where skill and luck can’t be so easily distinguished. That exact balance is unknown to any of us, as best we try. We can only try to approximate it and to use that approximation to perform slightly better than average through diligence and process. This goes for any form of decision making, but it is especially challenging when luck and skill are so intertwined.

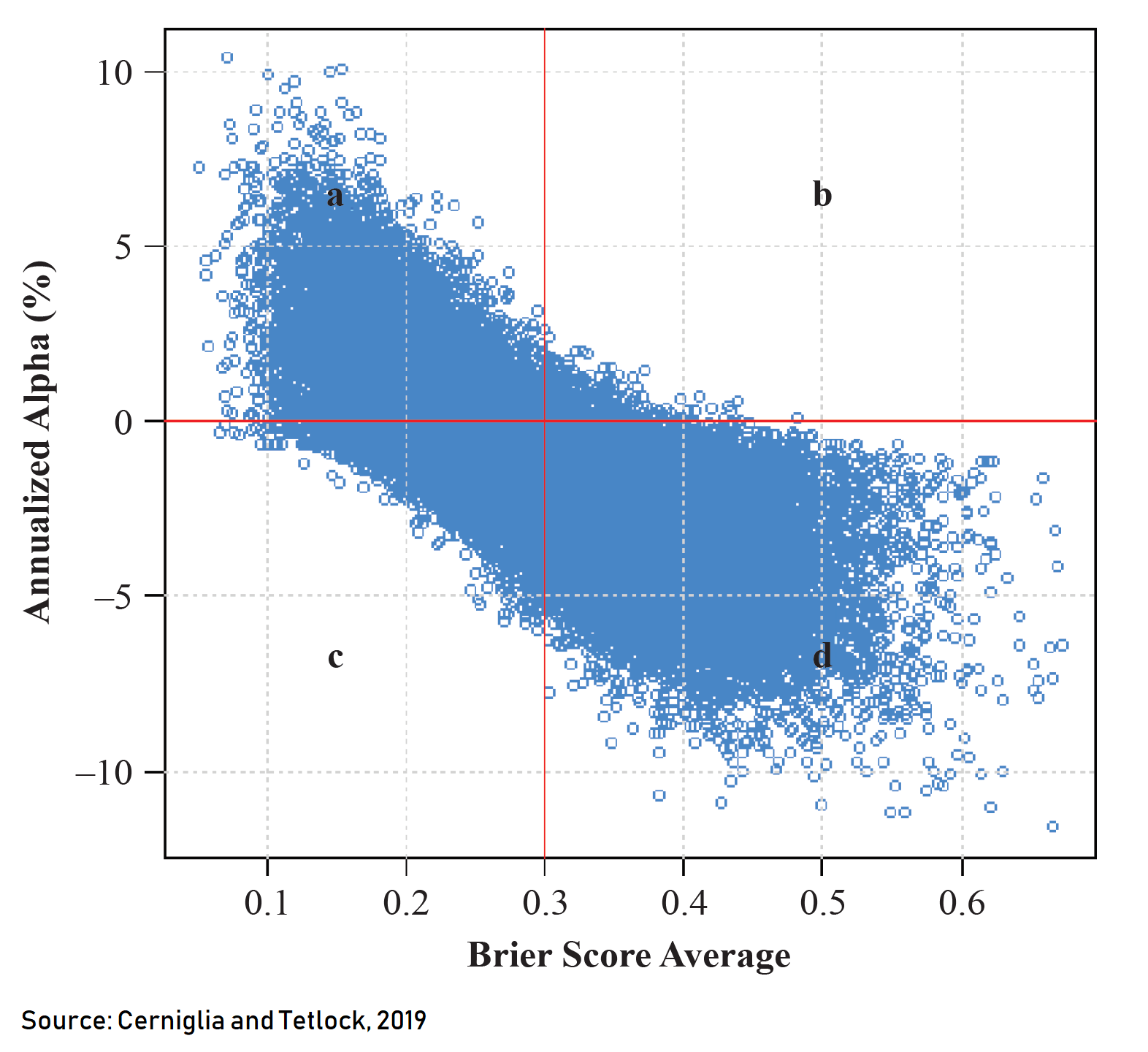

To visualize, take a look at this chart from Joseph Cerniglia and Philip Tetlock’s recent paper Accelerating Learning in Active Management. It shows a distribution of skill (x-axis) vs alpha (y-axis) across a simulated distribution of thousands of asset managers. First, one can see there is a strong correlation between true skill (represented by low Brier score) and alpha. This is good. But there is still wide dispersion. Certain high skill (low Brier) managers have very low alphas. Vice versa with low skill / high alphas.

Potential Solutions

What are we to do about this? Well a couple things. First, allocators need to baseline metrics before getting to stories. The smart ones we talk to increasingly do. Qualitative inference is valuable but must always be handicapped. Second, the entire ecosystem needs to carefully evaluate the principal/agent issues at play. Agency issues have run amok, especially when strategies are complex. Some great managers languish due to their inability to market complexity, and some storytellers make it out like bandits. Third, technology needs to address search/discovery costs. They are unusually high comparatively in an opaque and regulated industry.

Reading a book like Lake Success while on a marketing trip at the very least makes us think deeply about this little game we play; trying to be the alpha-peacock in the institutional beauty pageant. As managers, let’s strive not to tell stories and provide helpful metrics. It’ll make everyone’s lives a bit easier.

---

The information contained on this site was obtained from various sources that Epsilon believes to be reliable, but Epsilon does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. The information and opinions contained on this site are subject to change without notice.

Neither the information nor any opinion contained on this site constitutes an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, including any securities mentioned in any report available on this site.

The information contained on this site has been prepared and circulated for general information only and is not intended to and does not provide a recommendation with respect to any security. The information on this site does not take into account the financial position or particular needs or investment objectives of any individual or entity. Investors must make their own determinations of the appropriateness of an investment strategy and an investment in any particular securities based upon the legal, tax and accounting considerations applicable to such investors and their own investment objectives. Investors are cautioned that statements regarding future prospects may not be realized and that past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.